Over the years, I’ve studied, and attended lectures, about Jacob and the ‘Twelve Tribes of Israel’ living a good life in Egypt during the early days of their exile. This also includes studying about Moses and his rescue of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt hundreds of years later. The problem is that not much is mentioned about the span of time between these events. So, quite often, I was asked the question: “Why didn’t the Israelites leave Egypt before they became slaves?” And, although not answered in the Bible, it is a very good question that deserves consideration. We will attempt to suggest possible answers, but we need to understand the story first.

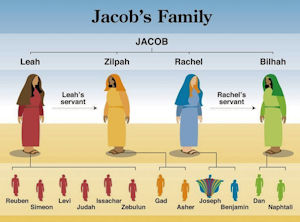

In the three Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), Jacob was the grandson of Abraham and considered one of the patriarchs of the Israelites. His story begins in the Book of Genesis, when he was one of the twins born to Isaac and Rebecca (Genesis 25:24-26). Later in life, God changed Jacob’s name to Israel (Genesis 32:27), and it is from him that the Twelve Tribes of Israel descended.

There were many times when someone’s name was changed in Bible times: because of a new relationship with God, to align a person to a new loyalty or status, or a change of nationality or religion, etc. An interesting article on this subject is “Why did some ancient people get their name changed?” It is listed at the end of this discourse in References & Notes.1

Now, Joseph (also known for having a coat of many colors), was one of Jacob’s sons, and there was not much love between him and his brothers. The story about Joseph indicates that he was sold into Egyptian slavery by his brothers. A detailed article about this event is titled “Genesis 37:3 — A Few Notes About Joseph’s Coat of Many Colors” and it is listed in References & Notes.2

Now, Joseph (also known for having a coat of many colors), was one of Jacob’s sons, and there was not much love between him and his brothers. The story about Joseph indicates that he was sold into Egyptian slavery by his brothers. A detailed article about this event is titled “Genesis 37:3 — A Few Notes About Joseph’s Coat of Many Colors” and it is listed in References & Notes.2

Eventually, Joseph rose in status from that of a prisoner in Egypt to become a powerful Egyptian leader under the Pharaoh (king). During a time of widespread famine, foretold by Joseph (with God’s help), he rescued his family by bringing all sixty-six of them (Genesis 46:26), plus their household staff, from Canaan to Egypt. They settled in an area called Goshen.3

Before Joseph’s father, Jacob, died, his last words were both a blessing and a prophecy for the sons and the tribes (clans) they would produce. These details, over time, all came true. After death, a royal funeral procession carried his embalmed body back to Canaan for burial.

Finally, the story about his son, Joseph, ends with his own death in the last chapter of the Bible’s first book (Genesis 50:22-26). The whole story about Joseph is covered in Genesis, chapters 37–50; it is an interesting, as well as educational, read.

This discourse also covers the very first part of the Book of Exodus, when there occurs a change of attitude toward the Hebrew people in Egypt. Joseph’s power and status were dependant upon his close relationship with Pharaoh, so when the king died, things began to change.

Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. He said to his people, “Look, the Israelite people are more numerous and more powerful than we. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, or they will increase and, in the event of war, join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land.”

Therefore they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor. They built supply cities, Pithom and Rameses, for Pharaoh. But the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied and spread, so that the Egyptians came to dread the Israelites. The Egyptians became ruthless in imposing tasks on the Israelites, and made their lives bitter with hard service in mortar and brick and in every kind of field labor. They were ruthless in all the tasks that they imposed on them. (Exodus 1:8-14, NRSV).4

This slavery continued until Moses (under God’s direction) successfully won the Hebrews’ freedom and brought them out of Egypt, some four hundred years after first arriving there. However, that event is another story for another time. All this is background information for the purpose of this article, which poses the question: Why didn’t the Israelites leave Egypt after the famine, before they became slaves? The land of Canaan was promised to them by God. Going to Egypt was to save their lives during the famine, so why didn’t they return after the famine was over?

A few thoughts about why they stayed.

Because of God’s promise of Canaan as a gift to his people, when Jacob was anxious about leaving, God also promised that one day they would return. So, the prominent thought is that they may have been waiting for a sign from God, before preparing to make the move back, after the famine was over.

God spoke to Israel in visions of the night, and said, “Jacob, Jacob.” And he said, “Here I am.” Then he said, “I am God, the God of your father; do not be afraid to go down to Egypt, for I will make of you a great nation there. I myself will go down with you to Egypt, and I will also bring you up again; and Joseph’s own hand shall close your eyes,” (Genesis 46:2-4).

According to the biblical narrative, there is no hard evidence indicating the Israelites’ slavery until it is mentioned in the Book of Exodus, but there were subtle tips about the Egyptians being prejudiced against them. Although the Hebrews were free to live on the land and to keep their herds and to do business with the Egyptians, they may not have been free to leave without permission or negotiation.

If you have read the story, you will note that Joseph had to request permission to leave and bury his father in Canaan. In allowing him to leave for the burial, Joseph made an oath to return. And those relatives who traveled with him had to leave their families behind, to ensure they would return. Besides, Egyptian palace personnel accompanied them on their trip.5

Later on, when Joseph died, his body was not returned to Canaan, but embalmed and placed in a coffin in Egypt. By that time, even if the Hebrews were persecuted, they were not enslaved, Pharaoh may not have liked them, but still did not allow them to leave. They may not have been treated equal, but their usefulness was depended upon by the government.

It was already known that their occupation of being shepherds was not a likeable quality. This was indicated when Joseph brought his whole family to Egypt and told his brothers, “all shepherds are abhorrent to the Egyptians.” (Genesis 46:34).

It was already known that their occupation of being shepherds was not a likeable quality. This was indicated when Joseph brought his whole family to Egypt and told his brothers, “all shepherds are abhorrent to the Egyptians.” (Genesis 46:34).

The Israelites lived in Egypt throughout Joseph’s remaining life, and for many more generations after he died. Pharaoh was agreeable with them occupying the land, so they were, somewhat, indebted to him. And he found them useful as contributors to Egypt’s prosperity during and after the famine.6

Famines don’t just abruptly end — they taper off gradually and the land and its people recover slowly. It must have taken a lot of time for the country to regain the prosperity of its former affluence. Pharaoh wouldn’t have allowed the loss of any contributors helping to restore the lifestyle enjoyed before.

Let’s face it, the Israelites had been cared for by Joseph, even during the famine. They enjoyed a relative comfort that the Egyptian citizens probably didn’t have. When the famine ended, they probably recovered swiftly and prospered in wealth and population — probably more so than the Egyptians. Of course, this was all through God’s blessings, but the Bible leaves blank the events during the coming generations and only brings the problems to our attention when they became dismal.

Outside Influences

There is another perspective to consider. During the famine, when the general Egyptian population lost all their possessions, they basically became slaves to the Pharaoh. If Pharaoh enslaved his own people, what would stop him from eventually enslaving the Israelites, too?7

Although absent from the biblical record, other historical evidence indicates a lot going on in that area of the world, during the time of the famine. About the time the Hebrews arrived in Egypt, there was also an invasion by the Hyksos. These Syrian-Palestinian people, who ruled northern Egypt,8 did not conquer the territory, but migrated there, possibly because of the famine. There was also an influx of people from the Mediterranean coastal cities, as well as from the expanding Hittite Empire from Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey).9

At some point, in their eagerness to rebuild their kingdom, the Egyptians turned on all these groups with a vengeance, forcing them into a state of servitude along with the Hebrews. There was probably also significant intermarriage between Hebrew and non-Hebrew peoples. “This would have swelled the ranks of the Israelites considerably.” Within a few generations, they probably were well integrated within the Twelve Tribes, “indistinguishable in language or custom, and all worshiping the God of Abraham.”10

At some point, in their eagerness to rebuild their kingdom, the Egyptians turned on all these groups with a vengeance, forcing them into a state of servitude along with the Hebrews. There was probably also significant intermarriage between Hebrew and non-Hebrew peoples. “This would have swelled the ranks of the Israelites considerably.” Within a few generations, they probably were well integrated within the Twelve Tribes, “indistinguishable in language or custom, and all worshiping the God of Abraham.”10

Joseph would have been a role model for intermarriage, as he had married an Egyptian woman, who was accepted into the family. Without this assimilation, there would not have been two million people (possibly more) leaving Egypt with Moses, carrying their possessions, as well as Joseph’s coffin with them. And those millions were only a fraction of the total enslaved, because the majority preferred to stay behind.

Some scholars believe most Israelites stayed behind because they were too comfortable in Egypt. They were born there, were already used to the place and conditions, and they were afraid to leave and face the unknown. The same thing happened to the Hebrews of Europe, those of Babylonia, and of the mass Jewish population dispersion in general.11

Real Evidence of a Famine

For some time, many archeologists and investigators did not believe Egypt had a famine, or that Jacob’s family lived in Egypt. But secular evidence is no longer lacking, as new research has shown. While there is no contemporary Egyptian record that the famine existed, an Egyptian text from the time of Greek ruling kings mentions a seven-year famine.12

And according to an article in the New York Times (30 March 2018), the Egyptians had anticipated the famine crisis during Joseph’s time and planned ahead, unlike other starving cultures and peoples desperate for food, during a period of drought. This event, during the reign of Ramses II, shows that the Egyptians planned ahead with “increased grain production in the greener parts of its empire [and they] crossbred cattle to produce a heat-resistant plow animal.”13

There is other evidence, too. A settlement dating from the late twelfth Egyptian dynasty has been found in the land of Goshen, where Jacob’s family settled. A small palace belonging to a high-ranking official was uncovered. The official was the ‘Overseer of the Fields’, who was responsible for the construction of numerous granaries.14

There is other evidence, too. A settlement dating from the late twelfth Egyptian dynasty has been found in the land of Goshen, where Jacob’s family settled. A small palace belonging to a high-ranking official was uncovered. The official was the ‘Overseer of the Fields’, who was responsible for the construction of numerous granaries.14

“The palace grounds also contained twelve tombs, all identified as Semitic burials. One of these tombs was originally covered by a pyramid, a very high honor reserved almost exclusively for royalty and unique in this period. Unlike the other tombs, this one is completely empty – no bones, no grave goods, nothing . . . this tomb contained [only] the remains of a statue of its owner. The statue is of an Asiatic (Semite) with red hair and wearing a multicolored coat.”15 It is a little remembered fact that Joseph’s genetic heritage included red hair (Genesis 25:24-26).

To Wrap Things Up

Early in Joseph’s storyline, he was sold into slavery by his brothers. Eventually, Joseph wound up in prison in Egypt. His release came after interpreting the king’s dreams. Pharaoh’s peculiar dreams involved seven thin cows eating seven fat cows, and seven ears of blighted corn swallowing up seven ears of good corn.

Pharaoh’s magicians (wise men) could not tell him what the dreams meant, but the chief cupbearer (butler) remembered that a man in prison could interpret dreams. They brought Joseph out and when he told Pharaoh what the dreams meant, it basically changed his life. He said this was God’s message that there would be seven years of plenty in the land, followed by seven years of famine. Pharaoh believes him and Joseph is released from prison and soon rises to the second highest office in the Egyptian government. You can read this part of his story in Genesis 41.

I have selected two songs related to these events. One is of the prisoner, Joseph, being brought before Pharaoh to interpret the dreams, and the other concerning both his pardon from imprisonment and the reward he receives. These songs are recorded from two scenes of the professional stage play of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.

I have selected two songs related to these events. One is of the prisoner, Joseph, being brought before Pharaoh to interpret the dreams, and the other concerning both his pardon from imprisonment and the reward he receives. These songs are recorded from two scenes of the professional stage play of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.

If you are not familiar with this performance, be aware it is rather weird. Back in the late 1960s, many people thought this stage performance was blasphemy, and even today, some few believe it so. But, hey, lighten up a bit! It was meant to be funny and was aimed at youth and the hippie movement and culture of the time.

Being a member of that rebellious generation, myself, I believe this stage play helped keep some hippies focused on the Bible, rather than the ‘New Age’ spirituality that was becoming the focus of many. To them, the Christianity of their parents was stoic and boring. This upbeat production was strange, but still got the biblical points across in a lively and positive way.

This musical comedy, with lyrics by Tim Rice and music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, tells the story of Joseph. First presented as a ‘pop cantata’ at Colet Court School in London in 1968, a stage production premiered on Broadway in 1982 and, later, on stages all around the world.16

Song #1 is ‘Song of the King’ when Joseph describes what the Pharaoh’s dreams mean. Song #2, ‘Stone the Crows’, is when Pharaoh frees Joseph and puts him in charge of preparing for the coming famine. Selected lyrics are below and video links for both songs are listed in References & Notes.

(Song #1)17

(Song #1)17

Well I was wandering along by the banks of the river

When seven fat cows came up out of the Nile, uh-huh

And right behind these fine healthy animals came

Seven other cows, skinny and vile, uh-huh

Well the thin cows ate the fat cows which I

Thought would do them good, uh-huh

Well this dream has got me baffled

Hey, Joseph, won’t you tell me what it means?

(Song #2)18

(Song #2)18

Well, stone the crows

This Joseph is a clever kid

Who’d have thought that fourteen cows

Could mean the things he said they did?

Joseph, you must help me further

I have got a job for you

You shall lead us through this crisis

You shall be my number two

![]()

Copyright © 2021, Dr. Ray Hermann

OutlawBibleStudent.org

→ Leave comments at the end, after ‘References & Notes’.

Your email address will NOT be published. For more information, click on “The Fine Print” on the top menu bar.

References & Notes

- Hermann, Ray, “Why did some ancient people get their name changed—and what is that about a white stone and new name for us?” (The Outlaw Bible Student, OBS, 11 June 2019), https://outlawbiblestudent.org/why-did-some-ancient-people-get-their-name-changed-and-what-is-that-about-a-white-stone-and-new-name-for-us/

- Hermann, Ray, “Genesis 37:3 — A Few Notes About Joseph’s Coat of Many Colors”, (The Outlaw Bible Student, OBS, 16 February 2021), https://outlawbiblestudent.org/genesis-373-a-few-notes-about-josephs-coat-of-many-colors/

- Goshen: land in the eastern delta of the Nile; lower Egypt. The Israelites lived there until they left during the Exodus, led by Moses.

- Unless otherwise noted, all references are from New Revised Standard Version Bible, (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989). Used with permission.

- “Vayigash – Why didn’t the family go back?” (Mi Yodeya, 5 January 2017), https://judaism.stackexchange.com/questions/78796/vayigash-why-didnt-the-family-go-back

- “Why did the sons of Israel stay in Egypt after the famine?” (Journey Revolution, 15 March 2009), https://journeyrevolution.blogspot.com/2009/03/why-did-sons-of-israel-stay-in-egypt.html

- Carasik, Michael, “Why Were the Israelites Enslaved?” (Torah Talk, 3 April 2012), https://mcarasik.wordpress.com/2012/04/03/why-were-the-israelites-enslaved/

- Aling, Charles, “Joseph in Egypt – Part VI” [The Shiloh Excavations], (Bible and Spade, Associates for Biblical Research, Summer 2003). Also, available online: (ABR, 9 April 2010), https://biblearchaeology.org/patriarchal-era-list/3913-joseph-in-egypt-part-vi

- Kramer, Howard, “Were there Egyptians among the Israelites of the Exodus?” (The Complete Pilgrim, 24 April 2016), https://thecompletepilgrim.com/were-there-egyptians-among-the-israelites-of-the-exodus/

- Ibid.

- Mizrahi, Maurice, “Why Didn’t Jacob Go Back to Israel?” (Torah Discussion on Vayechi, 31 December 2020), https://images.shulcloud.com/618/uploads/PDFs/201231-WhyDidntJacobGoBacktoIsraelVayechi.pdf

- Aling, Charles, “Joseph in Egypt – Part V” [The Shiloh Excavations], (Bible and Spade, Associates for Biblical Research, Spring 2003). Also, available online: (ABR, 5 April 2010), https://biblearchaeology.org/patriarchal-era-list/3477-joseph-in-egypt-part-v

- Feinman, Peter, “Archaeologists Confirm Ancient Famine: Déjà Vu Joseph All Over Again”, (Institute of History, Archaeology and Education, 15 April 2018), https://ihare.org/2018/04/15/archaeologists-confirm-ancient-famine-deja-vu-joseph-all-over-again/

- “Joseph”, (The Biblical Timeline, retrieved 21 May 2021), http://www.thebiblicaltimeline.org/joseph/

- Ibid.

- “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat”, (Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 24 May 2021), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_and_the_Amazing_Technicolor_Dreamcoat

- (Song #1) – “Song of the King”, Artists: Robert Torte (Pharaoh), Donny Osmond (Joseph), and Maria Friedman (Narrator/Singer); Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber; Lyrics: Tim Rice; Director: David Mallet; (from the film version of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, 26 November 1999; Universal Pictures, Really Useful Films, PolyGram Video) – MUSIC VIDEO #1: https://youtu.be/ToMHmDaPumc

- (Song #2) – “Stone the Crows”, Artists: Robert Torte (Pharaoh), Donny Osmond (Joseph), and Maria Friedman (Narrator/Singer); Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber; Lyrics: Tim Rice; Director: David Mallet; (from the film version of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, 26 November 1999; Universal Pictures, Really Useful Films, PolyGram Video) – MUSIC VIDEO #2: https://youtu.be/36LBJcQGfqQ

I wish to comment on the following paragraph.

If you have read the story, you will note that Joseph had to request permission to leave and bury his father in Canaan. In allowing him to leave for the burial, Joseph made an oath to return. And those relatives who traveled with him had to leave their families behind, to ensure they would return. Besides, Egyptian palace personnel accompanied them on their trip.5

My comments…

I cannot just leave my job, without telling my supervisor. If I do, after three days, my employment will be terminated. If I let my boss know, I can leave for several days (even a week or two) at a time. Also, if just the adults went to bury Jacob, the group could travel faster than with all their families. If the whole family went, what would happen to their herds of livestock?

Thank you for sharing your thoughts and opinions.

The guest who wouldn’t leave but instead stayed and got fat.

Thanks for stopping by and leaving a comment.

I’ve read this story from the King James Bible, but never with such clarity. Interesting. I will have my sons read it also. The order you’ve presented it was easily understood and I found it to be an easy, quickly and explained very well. Thanks!! I’m interested in others you may present.

Thank you for reading this article and for taking the time to comment; it is appreciated. And thank you, too, for your kind words. I pray this study will be of benefit to your sons.